Uneven Election Policies Across the Country Shape Youth Voting

Lead Author: Peter de Guzman

Contributors: Jamie Frye, Megan Lam, Alberto Medina, Sara Suzuki

CIRCLE research has consistently found that facilitative election laws can be critical to the political participation of young people, many of whom are newly eligible voters who can face logistical barriers to voting. Our studies have shown that policies like online voter registration, automatic voter registration, and pre-registration are correlated with higher youth voter participation. However, because these policies are enacted (or not) at the state level—and even similar policies can differ in their design and implementation—that means young people can have vastly different experiences registering and voting.

In August 2022, CIRCLE conducted a scan of electoral policies in all 50 states and Washington, D.C. to understand the context of youth voter registration and voting in the upcoming midterm elections.

We find:

- Since the 2020 elections, three states (Hawaii, Maine, West Virginia) have implemented new automatic voter registration (AVR) systems, which may contribute to a younger electorate in those states. New York and Delaware have also passed AVR but not yet implemented it in time for the 2022 election

- Four states have enacted more strict photo-ID requirements to vote since the 2020 elections

- Several states have moved to impose additional restrictions on vote by mail and absentee ballot drop-off

- Three new states (California, Nevada, and Vermont) have transitioned to all-mail elections, and approximately one in five young people live in a state that will conduct all-mail elections in 2022

Policy Changes Since 2020

Following the 2020 elections, many states have expanded access to different methods of voter registration and voting outside of Election Day, but others have implemented restrictive voter ID practices or limitations on mail-in voting.

Expanding Access to Elections

Rhode Island passed the “Let RI Vote Act” in June 2022. This legislation allows for no-excuse voting by mail, removing a previous witness or notary requirement, allows voters to request mail ballots online, and requires every municipality to provide at least one ballot drop box. In addition, Rhode Island made early in-person voting policies that were first implemented during the 2020 elections permanent.

Other states have enacted policies that may lower barriers for youth voter registration and increase youth participation. Virginia has implemented same-day registration, which may increase turnout among voters ages 18-24. Four states (DE, ME, NY, HI) have passed legislation to create automatic voter registration systems since 2020, and three states (HI, ME, WV) have implemented new AVR systems since 2020. Previous CIRCLE research has found that youth voter registration was higher in states with AVR. Maine passed legislation to establish online voter registration within the state (HB 804), but it will likely not be implemented until November 2023.

California, Nevada, and Vermont have moved to conduct all of their elections by mail, meaning that they will mail every registered voter a ballot for them to return via mail or absentee ballot drop-off. In 2020, on average, youth voter turnout was highest in states that automatically mailed ballots to voters.

New Restrictions in Several States

However, not all changes made since the 2020 election have removed barriers to voting and registration. In particular, states in the Western and Southern regions have imposed additional requirements on voting and registration that may have negative impacts on youth voter turnout. In June 2022, Missouri passed H.B. 1878, creating a strict photo-ID requirement, banning the use of mail ballot drop boxes, and imposing several restrictions on third-party voter registration organizations.

Including Missouri, four states (MO, WY, MT, AR) have enacted legislation that created new voter identification requirements, posing difficulties for young voters, many of whom may struggle with access to voter ID. In addition, at least six states (Wisconsin, Georgia, Iowa, Missouri, Texas, and Florida) have implemented new time and location restrictions on the return of mail ballots. Many young voters face barriers to voting related to time off work, transportation, and long lines at the polling place, putting them at risk of not voting if ballot return options are limited. Notably, Wisconsin, Georgia, and Florida have Senate races ranked highly on CIRCLE’s 2022 Youth Electoral Significance Index of where youth can have a big impact on election results—but this impact may be limited by restrictive voting and registration policies.

In-Depth: Specific Policies

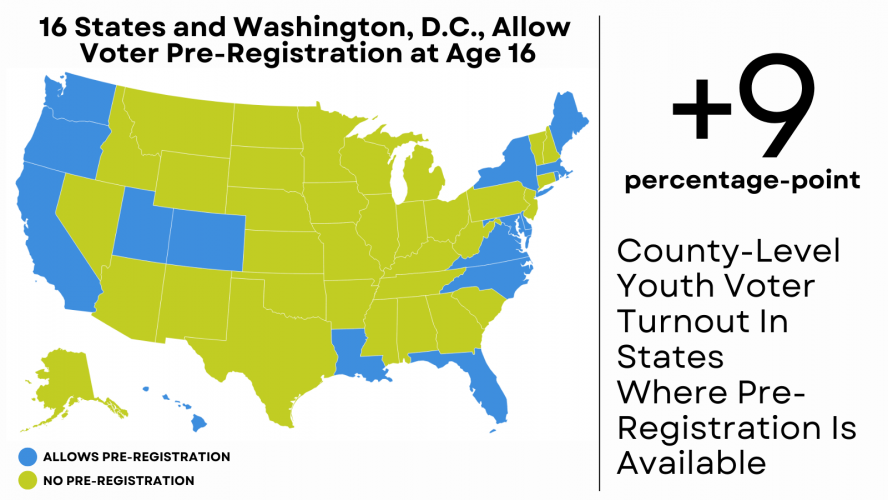

Why This Matters: Pre-registration allows young people to complete a voter registration application so they will be officially registered to vote once they turn 18. That can be helpful in engaging and registering the newest eligible voters, who often lag behind their slightly older peers in electoral participation. In fact, CIRCLE’s September analysis of youth voter registration data shows that most states are lagging behind their 2018 registration numbers for youth ages 18-19. We have also found that having a pre-registration law in place in 2020 was associated with a 9-percentage-point increase in a county’s youth voting rate.

Most states allow young people to register to vote if they will be 18 on or before the next election. In addition, some states allow registered young people who are under the age of 18 to vote in a primary election if they will be 18 years old on or before the following general election.

However, 19 states and Washington, D.C., allow all 17-year-olds to pre-register to vote regardless of their age at the time of the next election, and 16 states and Washington D.C. allow all 16-year-olds to pre-register to vote. This most expansive form of pre-registration is conducive to growing voters by helping young people prepare to become active participants in democracy from an early age—often while many are simultaneously taking a high school civics course.

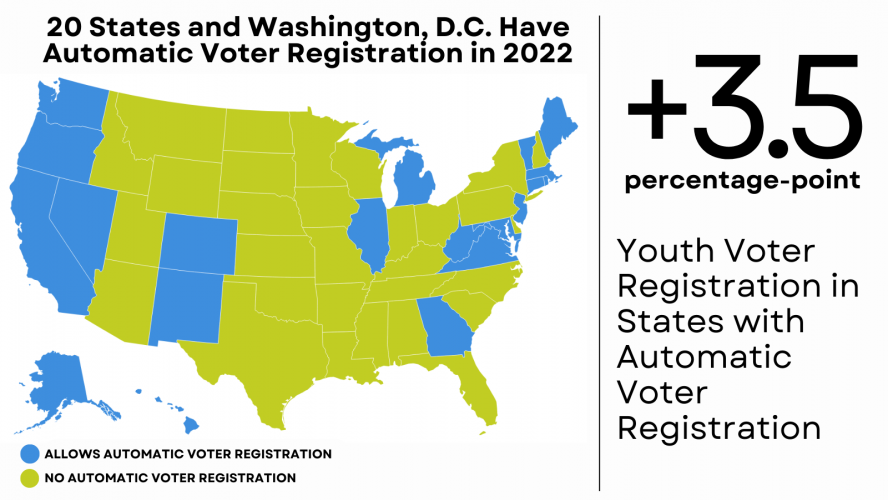

Why this Matters: Automatic voter registration (AVR) reduces barriers to voting by automatically registering eligible voters who complete an official transaction with certain state agencies, such as the Department of Motor Vehicles. Previous CIRCLE analysis of 2020 data found that, when controlling for factors such as education and income, voter registration among young people was 3.5 percentage points higher in states that had implemented AVR.

Twenty-two states and Washington, D.C., have passed legislation or otherwise approved the establishment of automatic voter registration, and automatic voter registration systems have been implemented in 20 states and D.C. This includes West Virginia, which had previously passed legislation to establish automatic voter registration in 2016, and implemented the system in 2021. Four other states (DE, ME, NY, HI) passed legislation to create automatic voter registration systems since 2020, but Delaware and New York have not implemented their AVR systems as of 2022 and are not included in the above map. Delaware’s AVR policy has a statutory deadline for implementation of 2023, and New York’s system is also likely to be implemented next year.

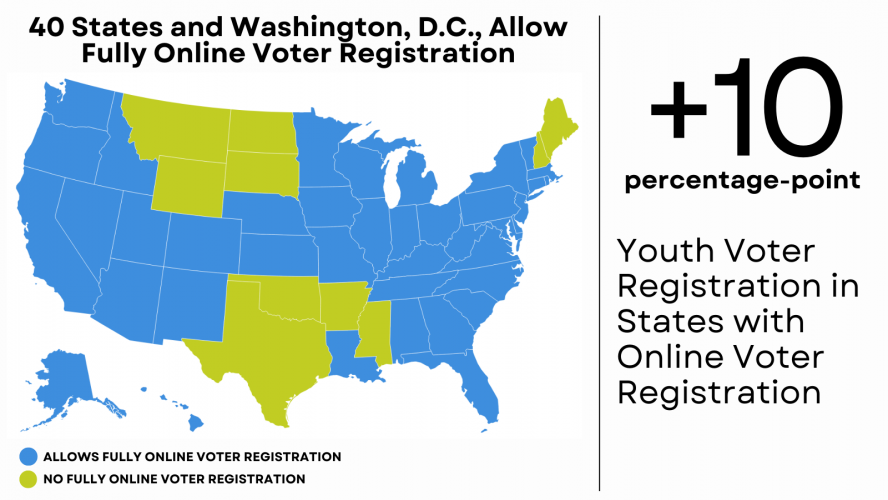

Why This Matters: Online voter registration (OVR) allows eligible citizens to register to vote by completing an online voter registration application. A previous CIRCLE analysis of 2020 data found that, when controlling for demographic factors such as education and income, youth voter registration was 10 percentage points higher in states with OVR.

Forty states and Washington, D.C. allow voters to complete voter registration applications through a completely online process for 2022. In addition, voters in Oklahoma who are registering for the first time can begin the process online but must print and submit their registration form by mail or in-person to complete their registration. In July 2021, Maine passed HB 804 allowing for online voter registration, but the state’s OVR system is not anticipated to be implemented until November 2023.

State-by-state implementation of online voter registration differs with regards to the required identification and the ability to complete the process completely online. Forty states and Washington, D.C., allow an eligible voter to complete their online voter registration application without printing any related documents. Thirty-seven states require voters to possess a valid driver’s license or in-state identification card to complete paperless registration. Only about half of OVR systems (21 states and D.C.) offer languages other than English on their online voter registration websites. Beyond expanding online voter registration to states where it is not yet available, addressing some of these additional potential barriers to access could facilitate higher and more equitable youth voter registration.

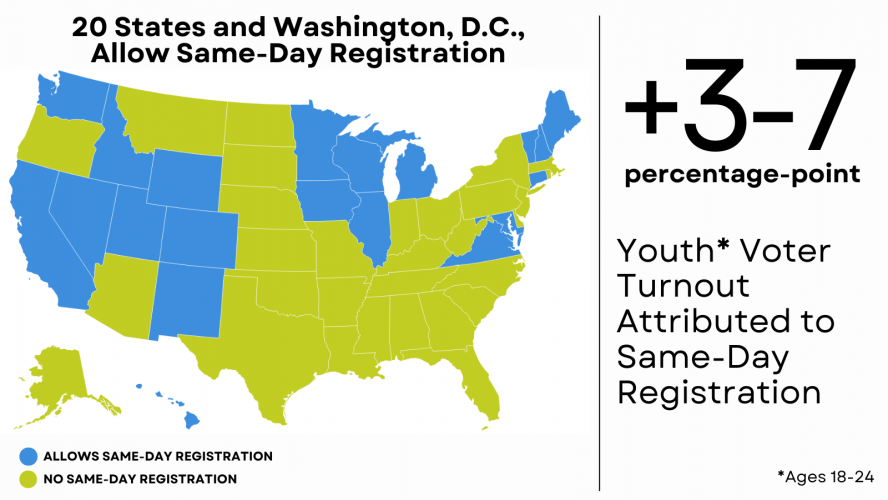

Why This Matters: Same-day voter registration (SDR) policies support young people, many who move often and need to register in a new state or update their address, by allowing them to register and vote at the same time. Some states allow for same-day registration just on Election Day, while others allow it during the early voting period. Research suggests that SDR may increase turnout among youth ages 18-24 and the availability of SDR in more states may lead to a younger electorate.

Twenty states and Washington, D.C., have implemented same day voter registration. That includes Virginia, which enacted Election Day registration in 2020 and implemented it on October 1, 2022, in time for the upcoming midterms. In July 2022, Delaware Governor John Carney signed House Substitute 1 to House Bill 25, which enacted same-day registration. However, in October 2022, the Delaware Supreme Court struck down HB 25, declaring the law unconstitutional and removing access to same-day voter registration in the state.

As with other electoral policies, SDR is implemented differently across states, which may cause confusion for some young voters. For example, Alaska and Rhode Island only allow SDR for voters voting for president and vice president, and these two states are not counted in the map above as having SDR in place for all elections. In 2021, Montana passed HB 176, which repealed the state's Election Day-registration law and moved the deadline to register to vote to the day before the election. That legislation has been the subject of an ongoing lawsuit. In September 2022, the Montana Supreme Court blocked implementation of HB 176, and a future ruling is expected.

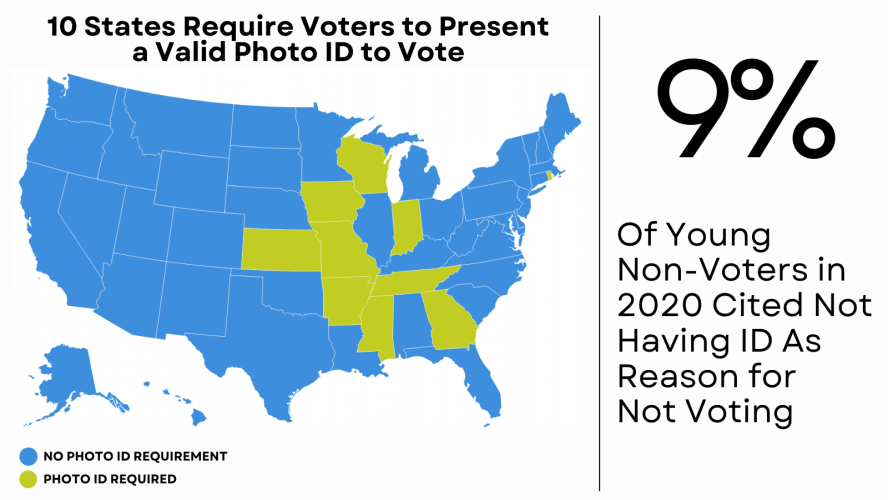

Why This Matters: Requirements regarding what identification individuals must present when voting vary by state, and research suggests that strict voter identification laws negatively impact the turnout of racial and ethnic minority voters. Currently, 10 states strictly require voters to present a valid photo identification document to vote. Four states (AZ, ND, OH, WY) require non-photo ID, such as a bank statement with a voter’s name and address. Previous analyses by CIRCLE found that youth of color were more likely than white youth to cite problems with voter ID as a reason why they did not cast a ballot.

Since 2020, four states (MO, WY, AR, KY) have created new voter identification requirements. Wyoming (HB 0075) and Kentucky (Senate Bill 2) passed legislation that requires voters to show government-issued photo ID to cast a ballot, although Kentucky allows voters without the proper ID to sign a “Voter Affirmation Form” and provide a different form of identification with their name. The only non-photo ID currently accepted to vote in Wyoming is a Medicare or Medicaid identification card.

Missouri and Arkansas removed exceptions to their photo ID policies. Previously, both states had allowed voters to complete a sworn affidavit to vote without presenting a photo ID. Now, neither state will allow that. The state also removed a religious exemption for providing photo ID to vote. Montana also passed a law with new, more restrictive ID requirements, but it was later struck down in court; however, a photo-ID requirement remains in place in the state (with other documents accepted for voters without current photo-ID).

Many states allow for voters who do not provide the proper identification to vote using a provisional ballot. However, this process may be unfamiliar to many young voters who may not know that they are legally allowed to request it. Even if a provisional ballot is used, voters may still be required to return at a later date and present qualifying identification for a ballot to be counted, with some states requiring voters to return as early as the next day with proper ID.

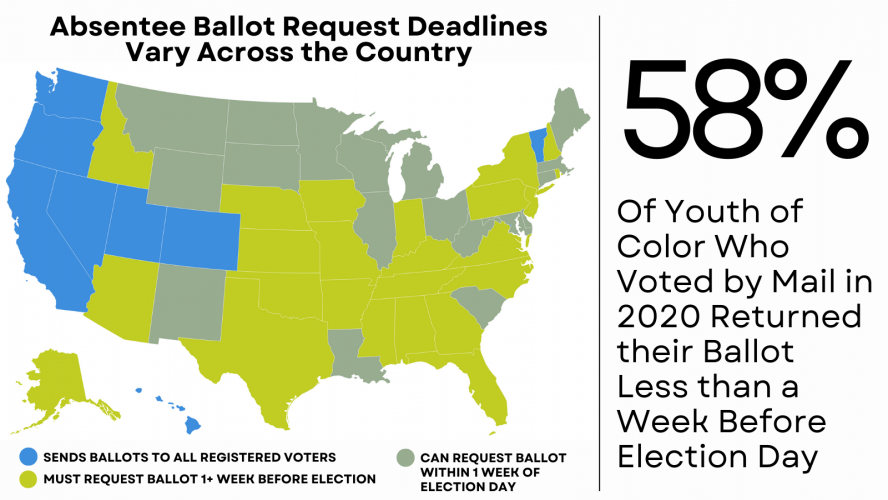

Why This Matters: Almost half (45%) of young voters reported voting by mail or absentee ballot drop-off in 2020. Following the 2020 elections, some states have codified the temporary expansions to mail voting that were implemented due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and other states have taken measures to increase access to mail-in voting. Previous CIRCLE analysis of the 2020 elections found that youth turnout was highest, and increased most, in states that automatically sent absentee ballots to registered voters.

California and Nevada now require that all registered voters receive a mail ballot, and Maryland now allows all voters to sign up to be placed on the permanent mail-in ballot list. Rhode Island has removed excuse and witness requirements to request mail ballots and now requires every municipality to host at least one secure ballot drop box. In Massachusetts, a new law makes mail-in voting a permanent option for voters, and mail voting applications (but not actual absentee ballots) will now be sent to all registered voters before each election.

With California, Nevada, and Vermont now conducting all of their elections by mail, according to the November 2020 CPS Voting and Registration Supplement, just over one in five (22%) youth ages 18-29 live in a state (or Washington, D.C.) that will conduct all-mail elections in 2022: CA, CO, DC, HI, NV, OR, UT, VT, and WA.

Notably, these all-mail states have higher proportions of Asian American youth and Latino youth than the national average. They also have smaller shares of Black youth than non-all-mail states and are below the national average. In 2020, we found that Black youth had less experience with mail-in voting, and the geographic disparity in where it is available may contribute to perpetuating that relative lack of familiarity.

Including those states that conduct all-mail elections, 35 states and D.C. allow for registered voters to vote by mail without providing an excuse. Nine states require an absentee ballot to be witnessed prior to its completion and return. Other states impose even heavier burdens: Missouri, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and South Dakota require absentee ballots to be notarized; Rhode Island and Alabama require absentee ballots to be notarized unless they are witnessed by two individuals.

Since the 2020 election, states like Wisconsin, Georgia, Iowa, Missouri, Texas, and Florida have enacted additional policies that may restrict access to voting by mail or absentee ballot drop-off.

On June 29, 2022, Missouri passed House Bill 1878, which banned ballot drop-boxes. Texas also signed a bill into law in 2021 that requires mail ballots that are dropped off by a voter to be received by an election official, effectively preventing the usage of ballot drop boxes. In addition, on Election Day, voters can only hand-deliver their ballot to the county clerk’s office; they cannot be returned to the voter’s local polling location.

These and other restrictive policies that threaten youth voting access could have a disproportionate impact on youth of color. Many of these states with more restrictive vote by mail policies are in the South, which has a higher concentration of Black youth than other regions of the United States. According to the 2020 Current Population Survey Voting and Registration Supplement, over one in three (37%) of 18- to 29-year-olds in Georgia are Black. Nearly one in three (32%) 18- to 29-year-olds in Florida are Latino. Thus, election laws and policies can be a matter of racial justice that promote or prevent equitable participation in a robust democracy.

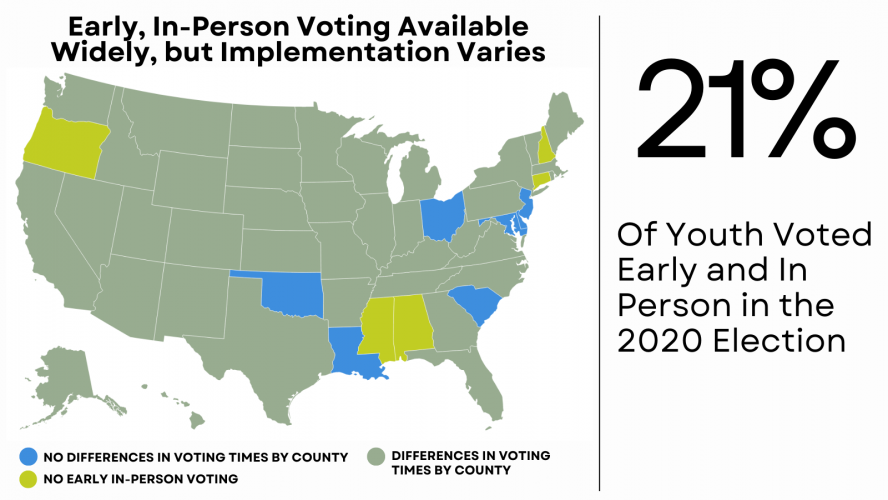

Why This Matters: CIRCLE analyses previously found that, in 2020, over 10 million young people cast ballots, before Election Day, either by mail or in person. Policies that allow voters to vote early in person differ heavily across the country. Many states offer early in-person voting, where a voter can vote at a polling place during certain hours on a certain number of days before the general election date, in a similar manner to how they would vote on Election Day. Other states offer early, in-person absentee voting, where voters arrive at an election office, request an absentee ballot, then complete and return the ballot in the same transaction.

Rhode Island’s “Let RI Vote Act”, passed in 2022, made early voting in the state permanent. Missouri’s House Bill 1878, though it included many policies that restrict access to voting and registration, went into effect on August 28, 2022 and authorized two weeks of early, in-person absentee voting. As of August 2022, only New Hampshire, Connecticut, Mississippi, Alabama, and Oregon do not provide in-person early voting options.

Some states have early voting periods at least two weeks before Election Day, but implementation varies by state and, in some states, even at the county or town level. Voting locations may close in the afternoon, be open on one weekend day but not both, or not open on the weekend at all. Sometimes this availability is written into law, but in 38 states CIRCLE researchers found that county election officials have discretion over the implementation of early voting hours and/or days in their state.

Some states (such as Indiana) offer in-person locations where voters are able to register to vote and vote early in the same interaction with the elections office. Colorado, which automatically mails ballots to all registered voters, also offers voting centers for those who do not want to vote by mail. Colorado voters can go to their county’s Voter Service and Polling Center to register to vote, update their voter registration, cast their ballot in person, obtain a replacement ballot, or drop off their mail ballot. Due in part to the many convenient options they offer voters, Colorado frequently has one of the top youth voter turnout rates in the nation.

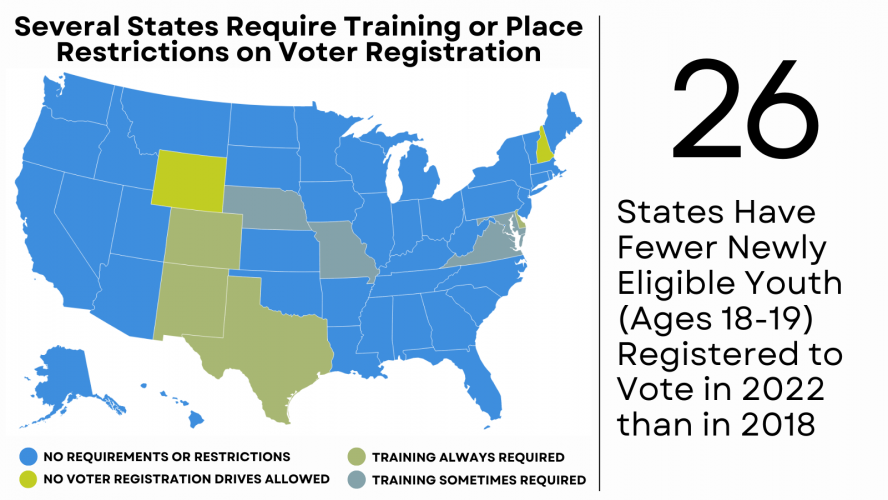

Why This Matters: Requirements for those conducting voter registration drives differ by state. Most states do not require training from the state before an individual or organization can conduct a voter registration drive and distribute voter registration applications. Some states require training and/or outline certain requirements for voter registration applications that are received in bulk. While training requirements may be well-intentioned and in some cases help inform citizens about voting laws and processes, they can also impose burdensome requirements that hinder important outreach efforts by individuals and organizations. Voter registration drives are often hosted by community and youth-serving organizations, whose outreach is critical to improve equitable youth participation.

Some states impose training requirements for voter registration efforts that collect over a certain amount of voter registration applications in a short time period:

- In Maryland, training becomes mandatory for those collecting at least 25 voter registration applications per day.

- Virginia requires voter registration drive participants to complete training if they request 25 or more registration applications from the Department of Elections.

- In California and Nevada, a registration or certification from the state is required if the organizer of a voter registration drive is collecting over 50 voter registration applications

- Missouri imposes many restrictions on third-party voter registration: its recently passed H.B. 1878 requires individuals who solicit more than 10 voter registrations to be over 18 years old and certified by the state, prohibits individuals soliciting voter registration applications from being paid, and prohibits individuals and groups from asking voters if they are interested in completing an absentee ballot application.

- West Virginia requires the submission of a request form if an organization or individual requests more than 10 voter registration applications. Oregon requires organizations requesting over 5,000 applications to develop a distribution plan that is shared with the Secretary of State when submitting the request form for applications.

Four other states (CO, DE, NM, TX) require training from the state for individuals to conduct a voter registration drive, regardless of the amount of voter registration applications collected. In addition, CO, DE, and NM each require all voter registration drives to be registered with state officials. Texas does not have requirements regarding the registration of voter registration drives or notification of election officials prior to conducting a drive, but it imposes additional requirements on the handling of voter registration applications.

For example: in Texas, volunteer deputy registrars may only accept applications from residents of the county where they are authorized as a deputy registrar, whereas other states do not have county-specific restrictions. Twenty-eight states have submission deadlines for forms collected at voter registration drives. Florida and Louisiana do not require those conducting voter registration drives to be trained, but all drives must be registered with the state. New Hampshire and Wyoming do not allow third-party voter registration, precluding the use of voter registration drives. Wyoming residents can register in-person at their county clerk’s office, or by mail. New Hampshire residents can register at their town or city clerk’s office, through a form mailed to them by their town or city clerk, or at their polling place on Election Day.

In Kansas, two third-party organizations, VoteAmerica and the Voter Participation Center challenged H.B. 2332 which included provisions to bar out-of-state organizations from encouraging voter engagement and sending Kansas voters mail voting application forms. After litigation, the state agreed to not enforce these provisions.

It is important for individuals and organizations who want to conduct voter registration to understand the legal requirements and restrictions in their state. Before the 2022 elections, Fair Elections Center and Campus Vote Project published updated voter registration drive guides for all fifty states and Washington, D.C.

Looking Forward

As we examine youth participation in the 2022 midterms, it is important to consider the potential impact of these policies on young people's voter registration and their access to the ballot box.

Going forward, to support youth voter participation and an equitable democracy, policymakers and election administrators should support facilitative election policies, such as automatic voter registration, same day registration, and vote-by-mail. They must also resist efforts to eliminate mail voting and absentee ballot return options, and photo ID requirements that disproportionately target young voters. In addition to passing facilitative electoral policies and supporting those already in place, election administrators must make information about these policies more accessible to young people. As detailed in the CIRCLE Growing Voters report, previous research has found that many young people are unaware of how to access voter registration or voting options in their state, have difficulty completing applications for ballots, and face other barriers. In order to grow voters, communities and institutions must work on transformative policy and cultural changes that center young people's electoral engagement.

CIRCLE Growing Voters

Released in 2022, the CIRCLE Growing Voters report introduces a new framework to transform how communities and institutions prepare youth for democracy. It includes major recommendations for organizations across sectors to do this work more equitably and effectively.