Growing Voters: Engaging Youth Before they Reach Voting Age to Strengthen Democracy

When more—and more diverse—young people are politically engaged earlier in life, they are more likely to remain engaged in the future and to be part of an electorate that is more representative of the country, which should be a key goal of our democracy. The 2018 midterm elections saw an extraordinary increase in youth participation, but the youngest eligible voters—those aged 18 and 19—still voted at significantly lower rates. That age disparity in youth turnout has long been intractable, but it is far from inevitable. At the national, state, and local levels, there are steps we can take to eliminate this gap and to move from a paradigm focused on merely mobilizing voters, to one centered on Growing Voters.

How We “Miss” the Youngest Eligible Voters

We don’t automatically become engaged, informed, and empowered to participate in our democracy when we turn 18. Instead, young people begin to understand and experience democracy, and what role they are expected to play in it, well before they reach voting age. Before youth reach 18, they can have (or miss out on) experiences and receive implicit or explicit messages that shape whether they believe their voice matters and that change is possible. They also may or may not get practical information about how, where, and when to vote. All of these factors are shaped by the specific community conditions that surround young people: in their town or city, school, neighborhood, etc. The availability and quality of opportunities to develop as a voter and active community member is frequently unequal across these settings.

Community Conditions Matter

With youth voting in particular, a vicious cycle has developed. Because, for decades, young people have voted at lower rates than those aged 30+, there are often negative media narratives that suggest youth are apathetic. Many young people get the message that they’re being dismissed. What’s worse, these narratives very rarely focus on the real systemic barriers young people can face. Every community has a variety of assets and constraints to creating a culture where engagement is encouraged and facilitated. Because of the way engagement is often set up or administered, those challenges can be especially acute for youth from low-income households and from communities of color. For example, school clubs, youth organizations, and other extracurricular activities can be important “incubators” of civic behaviors, but depending on their race and ethnicity, or socioeconomic status, young people may have very inequitable access to those opportunities.

Basic Voting Information Is Not Obvious or Ubiquitous

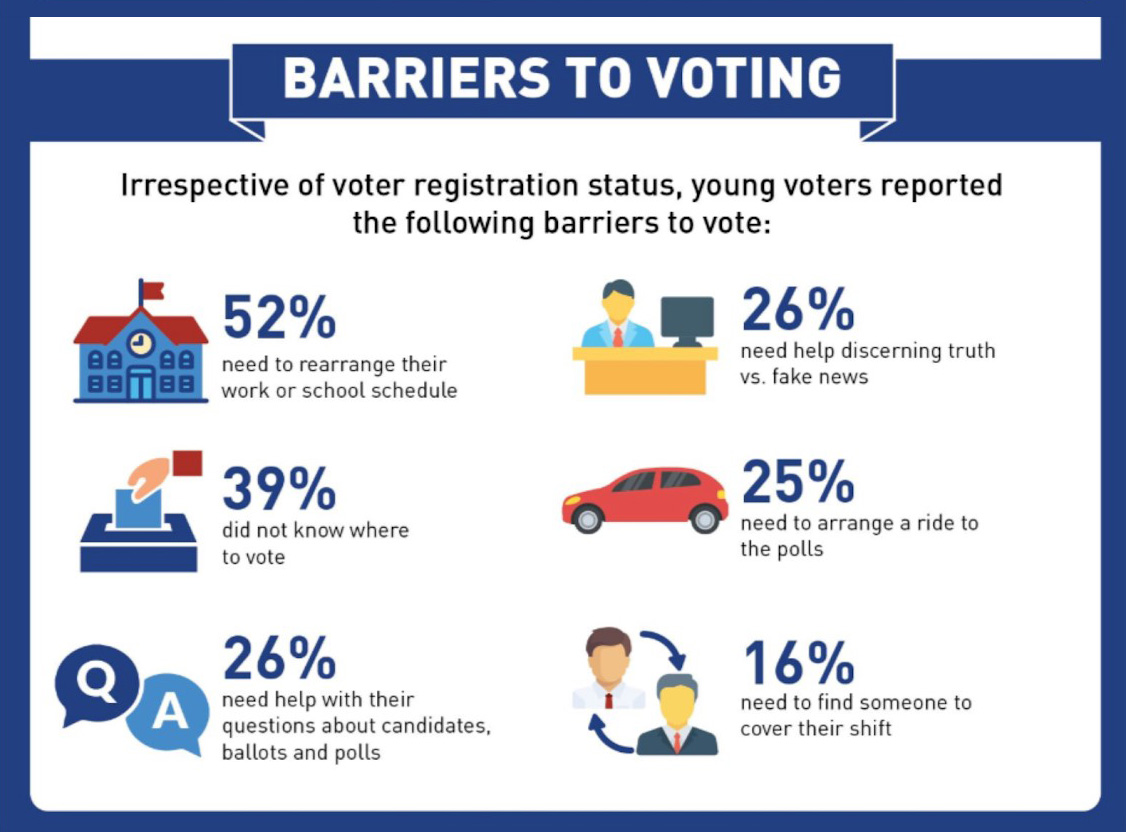

In addition, some young people don’t know basic information about elections and aren’t sure where to get accurate information, especially when it comes to local elections. As with other obstacles, this barrier to voting is exacerbated by broader inequities. In our recent study of low-income youth, 39% said they did not know where to vote. And while some young people can rely on family, co-workers of peers who are experienced voters, many others lack that support system and are unaware of other resources (like county or state elections office websites) where they could find out what they need. Election administrators can do more to understand issues of youth access, especially for young people who aren’t on college campuses.

Campaigns Aren’t Talking to the Youngest Eligible Voters

We can use the 2018 election cycle as a case study of how youth can get left behind by traditional electoral engagement strategies, and why we need a paradigm shift to increase and diversify voting among 18- and 19-year-olds, and youth engagement more broadly.

In our pre-midterm election poll, conducted in September 2018, we found that the youngest voters intended to vote at about the same rate as their slightly older peers: 31% of youth aged 18-21 said it was “extremely likely” that they’d vote, and 34% of youth aged 18-24 said the same. This suggests that the interest in casting a ballot was relatively equal among all youth and, far from being a product of apathy, the age gap in turnout is due to the various factors that influence whether someone who wants to vote actually does so.

One of the major factors is contact by political parties and campaigns. Research has shown that contact correlates strongly with voting, but campaigns reach out to the youngest potential voters much less, and less often. In 2018, for example, less than a third of young people aged 18-20 who were not in college and/or had no college experience were contacted, whereas 60% of 18 to 24-year-olds were contacted. There are several reasons: first, campaigns rely heavily on previous voter rolls when coordinating outreach, so newly eligible voters are frequently left out. In addition, many political campaigns focus their youth outreach efforts on college campuses, and 18- or 19-year olds who may still be in high school, new to college and still acclimating to campus life, or not college-bound, can miss out. These are systemic issues that call for broad-based solutions.

A New Paradigm: Growing Voters

While electoral reforms and campaign mobilization strategies that reach youth when they near or reach voting age are important, in order to achieve a more representative electorate and sustained increases in youth participation efforts to prepare young people for electoral and civic engagement must start much earlier. Young people’s ability and desire to participate are shaped by many factors throughout their childhood and adolescence, and many youth become political actors long before they turn 18. As young people showed last year, especially in the aftermath of the Parkland school shooting, youth are raising awareness about issues, leading movements, and persuading friends and peers—all while being affected by the decisions of their political leaders.

Many different people in a community can play a role in Growing Voters, and the strategies they pursue can shift given the resources and constraints in a given community. Here are some ways to advance the work of Growing Voters:

CIRCLE Growing Voters

In June 2022 we released a major CIRCLE Growing Voters report, which expands on this research and introduces a new framework for how to reach all youth, eliminate inequities in voter turnout, and prepare the next generations to participate in democracy.

K-12 Civics and Teaching about Elections

One key element of the Growing Voters paradigm is equitable, comprehensive K-12 civic education that incorporates teaching about voting and elections. Schools are uniquely able to reach nearly all youth in systematic ways, and to identify and address any gaps by race, socioeconomic status, etc. In our extensive research on the relationship between civic education and voting in the 2012 election, we found that teaching about voting increased the likelihood of students (self-reported) voting when they turn 18 by 40%. While more research on how districts and schools institutionalize this practice is needed, we know that there are ways to implement this beyond specific lesson plans. When schools and districts commit to teaching about elections and voting, it can reduce negative messages about politics and youth voice.

We know that educators can be hesitant to help students learn the ins-and-outs of the political process and of political participation out of fear of being accused of partisanship. However, it is possible and necessary for schools to reduce constraints on political engagement, create a climate that supports youth civic development, and incorporate non-partisan lessons that address the importance of voting and even the basics of how to fill out a ballot. Schools can also work with election officials and community-based organizations to facilitate voter registration for students who turn 18 and for younger students where pre-registration is available. CIRCLE coordinates a national alliance committed to supporting districts and schools’ efforts to create a school climate that support political learning and teach all students about elections and voting.

When implemented and properly supported statewide, a mandatory k-12 civics course that incorporates effective instructional practices can build young people’s civic knowledge, skills, and efficacy. Research has also shown that a civics test that is a graduation requirement can positively influence subsequent political engagement. (Importantly, this research did not include analysis of requirements to pass the American citizenship test, which some states have proposed or used as a civics test.) Relatedly, we recently found that 27 states now have language in their state codes that encourages, supports, and/or in a few cases requires a school or a local elections office to facilitate voter registration (and occasionally some basic education about voting, separate from course requirements and curricular standards) in high schools.

Facilitative Voting and Registration Laws

The 2018 election illustrates not just what’s not working, but what can make an impact. Youth voting, including turnout in 2018, can vary greatly at the state level. Youth turnout varied widely from state to state, including among 18- and 19-year-olds. While the national average was 23%, in six states (Colorado, Oregon, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada and Washington) the turnout rate for these “youngest youth” was above 30%. Five of those states (CO, OR, MN, NV, WA) have at least one of what we have termed facilitative election laws that make it easier for young people to register to vote and actually cast a ballot, such as automatic voter registration or pre-registration for youth before they turn 18. Our research has found that several of these policies have effects on youth voting:

- Online voter registration - A positive correlation between enacted state policy and turnout of youth aged 18-19, and a minor positive effect on the registration rate of that same age group

- Strict Photo ID laws - A negative correlation with the voter turnout of youth aged 18-29, especially among youth of color

- Pre-registration - A minor correlation with turnout for age 18-19 youth, but only if pre-registration is available for both 16- and 17-year-olds (as opposed to just for 17-year-olds)

Other state laws and codes that support, for example, having young people serve as poll workers and voter registration in high schools, can also strengthen youth electoral engagement . Full implementation of these policies across the country is an important goal and this can differ greatly at the state level and within a state.

Youth-Centered Election Administration

As with schools, there is election infrastructure in every county in the United States that has the opportunity to reach, inform, and prepare young people to participate in democracy. However, our research reveals that there are many youth who do not trust or feel welcome in election offices and don’t understand how to access information about registering and voting. Election administrators have a crucial role to play in recognizing and working to overcome the specific barriers a wide range of young people face. These officials must rethink and redesign election administration to take into account the specific developmental needs of young potential voters; in particular, officials should not take for granted that youth will know, know where to find, or be able to easily learn from family and friends, basic information about when, where, and how to vote. This can include materials and processes informed by youth experiences, partnerships with local youth organizations, and state-level programs and resources from a Secretary of State or Board of Elections that can contribute to helpful state-specific materials and a culture of voting.

One particularly promising initiative: Several states allow for 16- and 17-year-olds to work at the polls on Election Day. These initiatives have multiple benefits: first, election administrators often face a shortage of poll workers, especially bilingual poll workers. Second, young people get to see same-aged peers when they go to their polling place, which our research has shown can be an unwelcoming place for some youth. According to a 2019 Survey of Minnesota Student Election Judge Programs by the YMCA Center for Youth Voice and Minneapolis Elections, over half of the 107 Minnesota jurisdictions who responded engage high school students to serve as election judges.

CIRCLE is currently partnering with Opportunity Youth United to support three OYUnited community action teams to build partnerships with local election officials to close these systemic gaps.

Supporting Diverse Local Youth Leadership and Voices

Other commitments central to Growing Voters can be advanced outside of the classroom or the county clerk’s office. Communities can support peer-to-peer outreach, organizing, and activism by creating or supporting spaces and opportunities for youth to come together and act on issues they care about, and by offering guidance and resources while letting young people, themselves, take the lead. Many of the educational and administrative practices we’ve mentioned can advance this goal: whether having teens as poll workers or using pedagogical practices centered on the concerns and ideas of youth. But just as important are community-based opportunities that can be led by youth, and that often provide opportunities for young people, especially those who have been marginalized, to develop critical consciousness and feel empowered to act.

Additionally, as civic institutions, media outlets also have roles to play in the work of bringing more community members into our democracy. Members of the media should interrogate narratives that suggest youth are politically apathetic, and they should focus on including more—and more diverse—young voices. Incorporating these voices can expand and enrich the stories being told, show other youth what their peers can achieve, and resonate with an audience that is often skeptical about the value and trustworthiness of media, especially their local news.

Final Thoughts

The efforts and policies described above are only at their most effective in facilitating youth participation when they are implemented deliberately, with an eye toward quality and equity, and with mechanisms in place for evaluation and accountability. As such, most of these laws and initiatives require adequate funding for training, professional development, and/or staff time.

Young people are not just the future of our democracy; they’re a big part of its present. In every field, in every community, and in every sector of our society, all of us have a role to play in Growing Voters and ensuring that youth are fully prepared to contribute to the political life of the country. For 2020 and beyond, we can begin that work and start seeing its impact today.