Discussion, Debate, and Simulations Boost Students’ Civic Knowledge

Ten years ago, the Civic Mission of Schools report (Gibson & Levine, 2003) clarified goals of civic education and identified six “promising practices” of civic education pedagogy. Three of these practices were measured on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) Civics test in 2010: discussing current events, debating current issues (including controversies), and participating in simulations of democratic processes and procedures.

In a new fact sheet, we explore who had access to three of the promising practices, whether these instructional practices were associated with higher NAEP Civics scores, and whether the effects of these practices varied for different demographic groups.

Significance

This new fact sheet addresses two important questions for civic education:

- Do discussion, debate, and simulations boost NAEP scores? If they do, that is a strong argument for using these approaches. If they do not, educators may face a tradeoff between teaching the concepts tested on the NAEP and using interactive civics pedagogy for other purposes, such as to teach deliberation skills and current events,

- Who gets these experiences?

The NAEP Civics assessment only measures certain kinds of knowledge: predominantly, abstract knowledge about perennial features of the US political system. The promising practices recommended by the Civic Mission of Schools have additional major objectives, such as teaching current events deliberation and collaboration. Furthermore, the NAEP’s criteria for “proficiency” are somewhat arbitrary (see this CIRCLE Fact Sheet for more details). However, the NAEP Civics is a well-validated and widely cited test of civic knowledge, given to a representative sample of over 26,000 students. The test is administered every three to four years, and latest assessment occurred in 2010.

Findings

At the 8th grade and 12th grade level, White students and students from higher socioeconomic backgrounds received more of the promising practices.

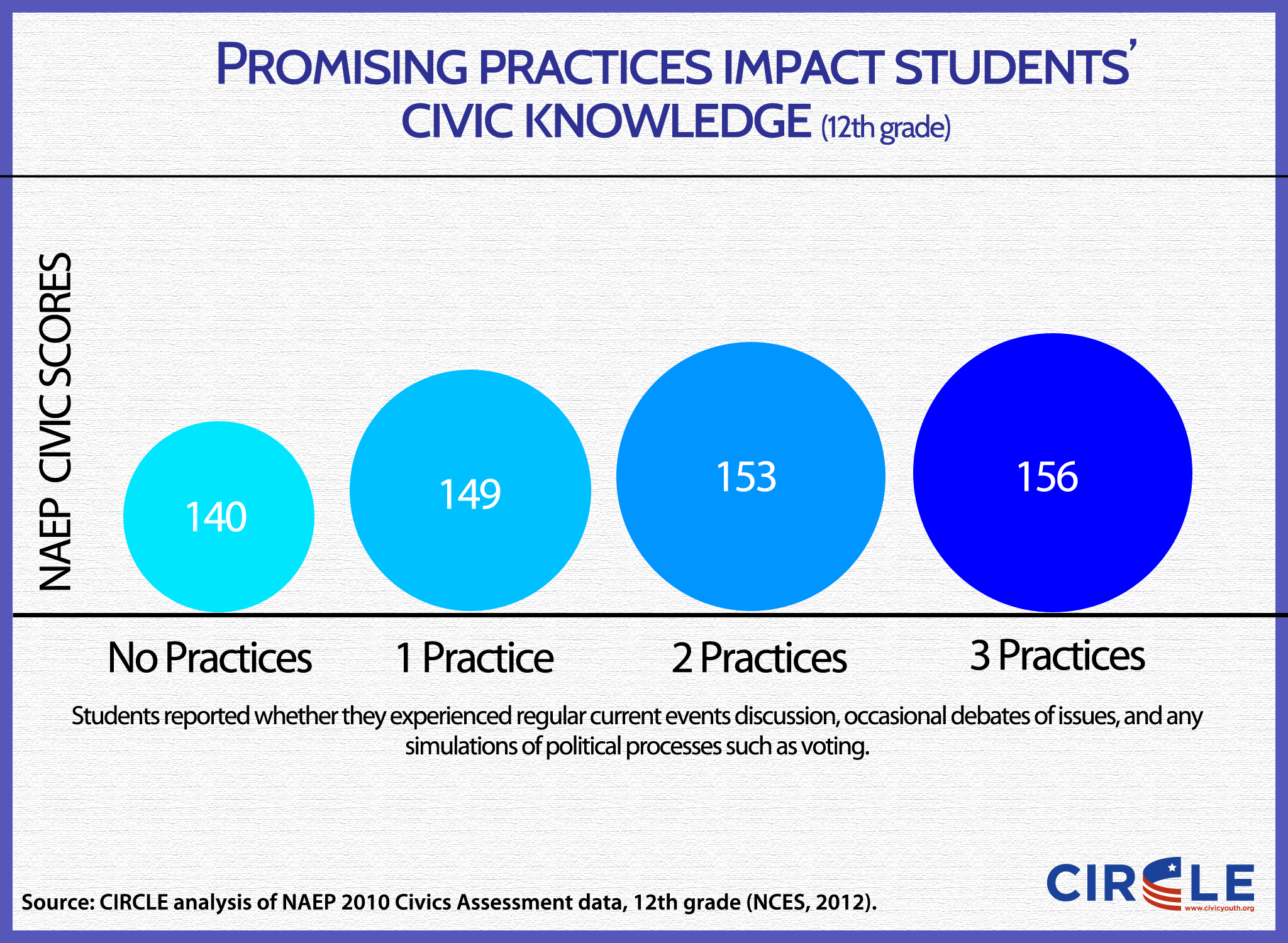

Exposure to these practices was associated with higher NAEP scores for all groups. The overall trend is that all groups benefited at least to some degree from the promising practices.

Unfortunately, exposure to promising practices did not reduce the race- and class-related achievement gaps in NAEP Civics performance. In most cases, advantaged students appeared to gain more than less advantaged students did from receiving these experiences. That means that if these practices were offered to all students, gaps in NAEP civics scores would actually grow.

At the 4th grade level, the promising practices were associated with lower NAEP scores, raising questions that require further research. The 4th grade students may not report the pedagogies they have experienced accurately, or elementary-grade teachers (with very limited time to teach civics) may face a tradeoff between teaching facts about civics and providing opportunities for dialogues about current events and simulations of civic practices in class.

Summary/Implications

- Middle- and high-school students of various backgrounds benefitted from receiving promising practices.

- Uneven distribution of promising practices across the economic and racial spectrum continues to be problem, as these practices benefitted students from all backgrounds.

- The practices did not have a clear benefit for 4th graders, and there is no evidence that disadvantaged 4th graders were less likely to receive promising practices, a finding that calls for more research.

- Civic achievement gaps were generally larger when students were exposed to the highest dosage of promising practices.

Future research should explore why less advantaged students did not gain as much from the recommended practices, at least if the outcomes are civics knowledge scores rather than motivations and skills, which are unmeasured by the NAEP. The disadvantaged students did benefit, so this finding does not provide a reason to reduce the promising practices in classrooms that serve them. However, it may be that closing chronic gaps in civic engagement will require more than just providing good pedagogy in civics classrooms. Professional development and other support for teachers, culturally appropriate materials and examples, and opportunities to learn and practice civics outside the classroom may also be necessary.