A Sense of Belonging and a Positive School Climate Are Key to Building Youth Political Efficacy

Authors: Kelly Siegel-Stechler, Noorya Hayat, Alberto Medina

Contributors: Katie Hilton, Sara Suzuki

A strong civic education is the foundation for lifelong civic engagement. When students acquire the knowledge and skills required for civic participation, develop democratic attitudes and dispositions, and learn to use their voice in order to have an impact on their communities, they are more likely to vote later in life and take part in other forms of civic engagement.

Extensive scholarship, including CIRCLE’s own research, underscores this association between civic learning and participation. We have found a link between high school civics courses and increased political participation and knowledge. More recently, we found that young people who are encouraged to use their voice in and out of the classroom were more likely to say that they would vote in the 2024 election.

In this new analysis, based on data from CIRCLE’s post-2024 election survey, we delve deeper into the influence of school climate on young people’s civic development and find evidence for its impact on students’ civic and political efficacy later in life. We examine elements of that school climate beyond student voice, especially a sense of belonging, and we connect them to additional measures of political efficacy and positive views about democracy and civic engagement.

Our analysis confirms that when young people experience a strong democratic culture in school that promotes their civic development, they score higher on measures of political efficacy. Unfortunately, our research also reveals that there are inequities—especially by socioeconomic status—in who benefits from those positive experiences in school, which may be contributing to disparities in voting rates and other forms of civic inequality later in life.

Many Students Aren’t Enjoying a Strong School Climate

We asked survey respondents (ages 18-34) to recall their experiences in high school and answer questions about whether they felt a sense of belonging, were encouraged to use their voice and express their opinions, and had input on decision-making. Overall, only about half of young people agreed or strongly agreed that they enjoyed most of those elements of a civic and democratic school climate. The exception was meaningful input in school decision-making; only a third of young people agreed they had that kind of influence in their school.

Based on that data, we created a “School Climate” scale that would allow us to measure the strength of that climate for youth overall and for various groups of young people. Overall, the average School Climate score for the entire sample was 3.29. We identified some differences by factors like race/ethnicity: for example, Asian youth scored 3.51, while multiracial youth scored 2.95. There were even larger differences by factors like gender and sexual orientation: straight youth scored 3.34 while queer youth scored 3.14, and gender minorities (youth who identified as neither men nor women) scored 2.93.

Some of the biggest differences arose when we examined this data by financial situation. Research has usually focused on the association between socioeconomic status and youth civic engagement, but our data makes it clear the association may extend to other aspects of a young person’s civic opportunities and development especially in school. Youth who told us they have significant financial resources and wealth scored 3.43 on our School Climate scale. While youth who said they often struggle to meet basic financial needs scored lower (3.11).

While we asked about young people’s situation now, which may not necessarily indicate their socioeconomic status while they were in high school, we believe these differences are indicative of major inequities in who has access to strong civic learning opportunities and a strong civic culture in school.

Strong Link Between School Climate and Political Efficacy

Using the School Climate score, we were able to study the link between young people’s civic experiences in school and their “political efficacy.” This measure is based on responses to eight different questions on whether young people feel well-qualified to vote and participate in other political activities, feel they have a good understanding of political issues, and believe they can make a difference through their own actions or by working with others.

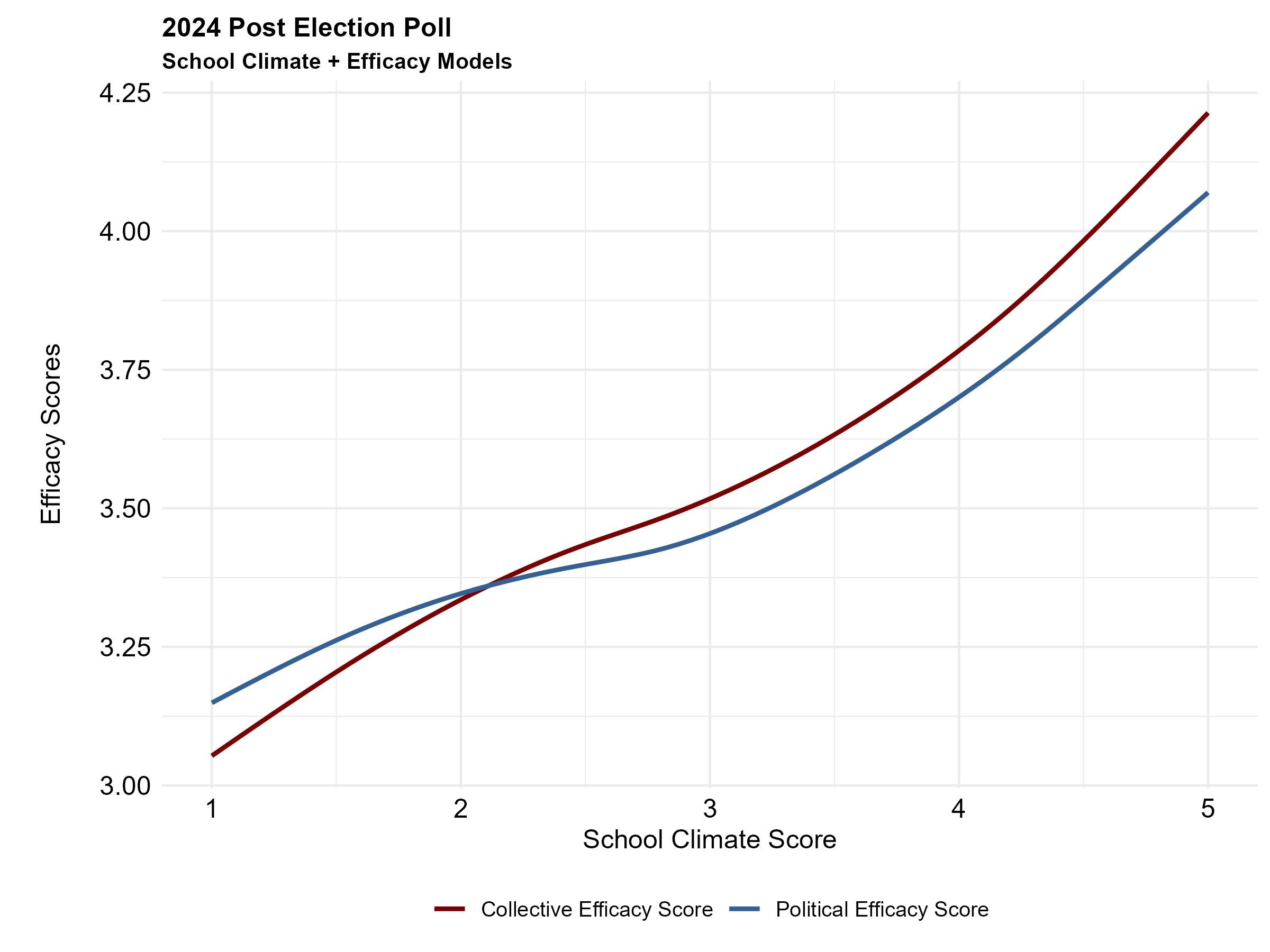

Our analysis finds that, even after controlling for race, gender, sexuality, and socioeconomic status, there is a strong positive association between school climate and political efficacy. The positive association is even stronger when it comes to the questions about “collective efficacy,” which measures young people’s sense that they can work together to solve problems and effect change, based on their answers to questions about taking action with others in their community.

These findings are significant because political and collective efficacy are associated with a range of positive civic outcomes, including voter turnout rates. Our analysis highlights that a strong school climate in which young people develop and use their voice, and feel a sense of agency and belonging, is key to preparing young people for democratic engagement later in life.

A Spotlight on Belonging and Ideas of Citizenship

Our analysis also shines a light on one of the measures that make up the School Climate scale, which asked youth whether “they felt that they were part of a community where people cared about each other” in high school. This measure, which we summarize as “belonging”, underscores the fact that civic learning goes beyond the acquisition of skills and knowledge, and includes a school culture in which young people feel supported and valued.

Less than half of youth in our survey (48%) said they recalled feeling that sense of belonging in school; that, in and of itself, should ring alarm bells about the school climates youth are experiencing. And there are deeper inequities by race and other factors when it comes to belonging than for the full School Climate score. Fifty-six percent of Asian youth and 50% of white youth said they felt belonging in high school, compared with 40% of Latino and 30% of multiracial youth.

We again see major gaps by financial situation: 48% of youth who are financially secure and comfortable felt a sense of belonging in high school, compared to 39% of youth struggling to meet basic financial needs.

These inequities are troubling because, according to our analysis, that sense of belonging in high school is strongly associated with positive views about what constitutes being a good citizen. Young people who agreed or strongly agreed that they felt a sense of belonging in school were 16 percentage points more likely to say that voting in national and local elections, or participating in local government in other ways, was very important to being a good citizen. They were also more likely to say that participating in local civic organizations, and taking part in activities like volunteering to help other people, are key to good citizenship.

Our data suggests that, by creating a climate in which students feel that people care about each other, schools may be instilling caring and support as a civic value, with broad implications for future civic and political engagement. Given the findings about voting as a form of good citizenship, youth appear to understand that electoral participation is a way to express and live that value of caring for their peers and communities.

Conclusion

This new analysis, and CIRCLE’s broader research, underscores that K-12 schools can be effective in preparing young people for democratic participation. That role goes beyond offering civic courses and other curricular opportunities, which are critical, but must also include a school climate that fosters a sense of belonging and helps young people develop and use their voices.

This is the work of Growing Voters—CIRCLE’s framework for how various institutions can strengthen youth civic learning and engagement in order to advance a more representative electorate and create a more equitable democracy. As one of the key institutions in young people’s lives, K-12 schools have a powerful role to play in Growing Voters both in and out of the classroom. A holistic focus on all aspects of students’ civic learning experiences can help ensure that schools are fulfilling their mission to educate students for civic participation and democratic engagement